The Next Novella

- July 31 2022

- 11 min read

“The novella is slender but gaping. It embraces pause and pattern and gesture. It declares, ‘I can say more with less’ and then it does.”

The Novella Is Not The Novel’s Daughter: An Argument in Notes - Lindsey Drager

The novella has a surprisingly rich history as a literary form. The term originated in 14th century Italy, most notably with Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron, establishing the novella as a collection of short tales based on local events and unified around a common theme. During the late 18th, 19th, and early 20th centuries, the novella experienced a revival by German writers who redefined its focus (framed around a real or imaginary event, brief and self-contained plots, a Wendepunkt or turning point in the story, and an objective presentation) 1 2. Eventually taken up by Russian and English authors, the novella has since been embraced for its constraints, both technical and narrative.

Don’t be fooled by their size, though. Despite their word limits, novellas can have a considerable cultural impact. Works like Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis, George Orwell’s Animal Farm, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince, and Ira Levin’s The Stepford Wives continue to enchant new readers… alongside excellent contemporary works like Cassandra Khaw’s A Song For Quiet, Victor LaValle’s The Ballad of Black Tom, Nnedi Okorafor’s Binti, and Becky Chambers’s To Be Taught if Fortunate. More digestible than a novel and more substantial than a short story, novellas “transgress its own limits, and hence the limits of fiction, to impact the world of its reader,” writes Florian Fuchs, and that “no matter what her interpretation, each reader will be left with an unresolvable residue at the end.”

So where are the video game novellas?

One Game Fits All

To be more specific, why don’t narrative video games have their own formal genre or category to identify works of a determinate length? There are plenty of games already that could be labelled under the ludic equivalent of novellas, but for whatever reason, as a medium, we have failed to find a common term for them. Or works of any length, for that matter. Aside from “minigame” and “microgame,” “video game” is the only term we have in our shared vocabulary that covers the gamut from 80-hour AAA blockbusters to 20 minute independent narrative experiments. And the absence of such terms feels even more glaring when comparing video games to other media.

In literary forms alone you can find flash fiction, short stories, novellas, and novels, for example, with a general agreement on the length of each one. In film, there are feature length films and short films, and in scripted television, you can find full series, limited series, and made-for-TV movies. Across all of these examples, there’s a consensus about the length of each category that sets up audience expectations, and provides creators with an array of viable options to tell the story they want to tell, in a way (and in a length of time) that best serves its purpose.

So why don’t narrative video games have formal genres to convey their length, too?

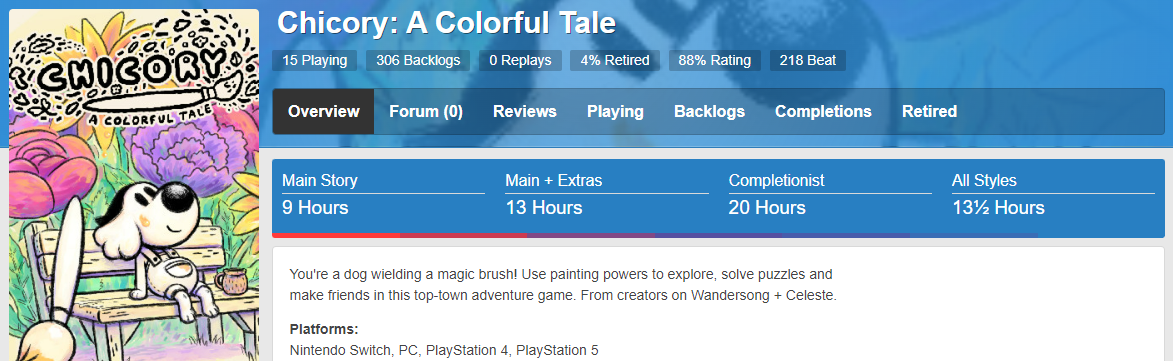

Well, first off, data on video game length isn’t as readily available compared to other media. Unless the information is printed in marketing copy (which you need to scan through to find and hope is accurate), your alternative is searching up the title on HowLongToBeat.com and hoping that enough players have logged in their data to give an accurate reading. But what happens if you want to quickly search for new games on Steam that can be played in a couple of hours? Or to look for games in the Nintendo eShop that can take 60 hours to complete? Or Playstation games that can be played in 15-30 minute sessions?

Have you played Chicory yet? You should play Chicory. Not enough people have played Chicory.

For some developers disclosing game lengths feels like a step too far, as recounted in Ben Lindbergh’s piece on The Ringer. Writer Anna Megill warns, “There’s a danger in viewing games as a time investment rather than an experience.” Ian Bogost pushes back against “the idea of needing to enumerate game length explicitly,” a decision that could reinforce the playtime-per-dollar arithmetic gamers typically make. Others argue that completion times act as a ticking clock that diminishes “the thrill of discovery,” and that games, as interactive media, should be treated as more than basic “obstacles to be beaten.” What about games with no definitive narrative endings? they ask. What about esports games? Can they even be quantified? Should they?

An Interactive Debate

This is one of those situations where, like accessibility settings in games, disclosing game lengths can offer more potential good for the people who depend on it than the mild annoyance it’ll provoke among a small subset of players. The argument that potential players may start seeing games as time investments also ignores the reality that a lot of games are very demanding of our time already, perhaps excessively so. Movies have the benefit of falling in the range between 90 minutes and 3 hours, enough to fill an afternoon or an evening. Books, though they require longer to read them front-to-back, have the advantage of being able to be effortlessly picked up and set down for short bursts of reading. Games, on the other hand, require ramp-up (such as loading times, warming up reflexes, remembering complex controls or what your last course of action was) and wind-down (such as having to locate in-game save points before exiting) which can be unforgiving for those who can’t dedicate themselves fully for long stretches of time. Being upfront about the time commitments we’d need to make for them is the least they can do.

Honestly, it’s easy to forget that movie runtimes are so common that they’re usually shared in the same breath as its year of release and genre (i.e. Dune, 2021, Sci-fi/Adventure, 2h35m). Books give readers a tangible and approximate indication of how much time we can expect to spend with them by their page count and font size. On eReaders, digital books display their completion percentages and estimated time left to read (which is a huge boon to readers who have trouble finishing books or need that extra motivation). These imaginary “ticking clocks” are simply there to help us better plan our time around them, for those people who need it.

Would it even be possible to get accurate runtime estimates for games? Well, for the most part, I believe it can. Developers usually have a sense for how long their games or play sessions will take to complete, given particular playstyles, either from explicit preproduction goals or from data collected during testing phases. More than self-reporting, a consumer watchdog group would also likely need to step up to verify playtimes through a standardized process, as Lindbergh goes on to explain. An organization like the ESRB, which rates games for their content much like the MPAA for movies, could potentially take on this responsibility. No matter the specifics here, the purpose isn’t to pin games down to an exact number but rather to provide an approximate range they can fall under, similar to HowLongToBeat’s system (such as Main Story and Completionist runs). Hey, a rough estimate is better than no estimate at all.

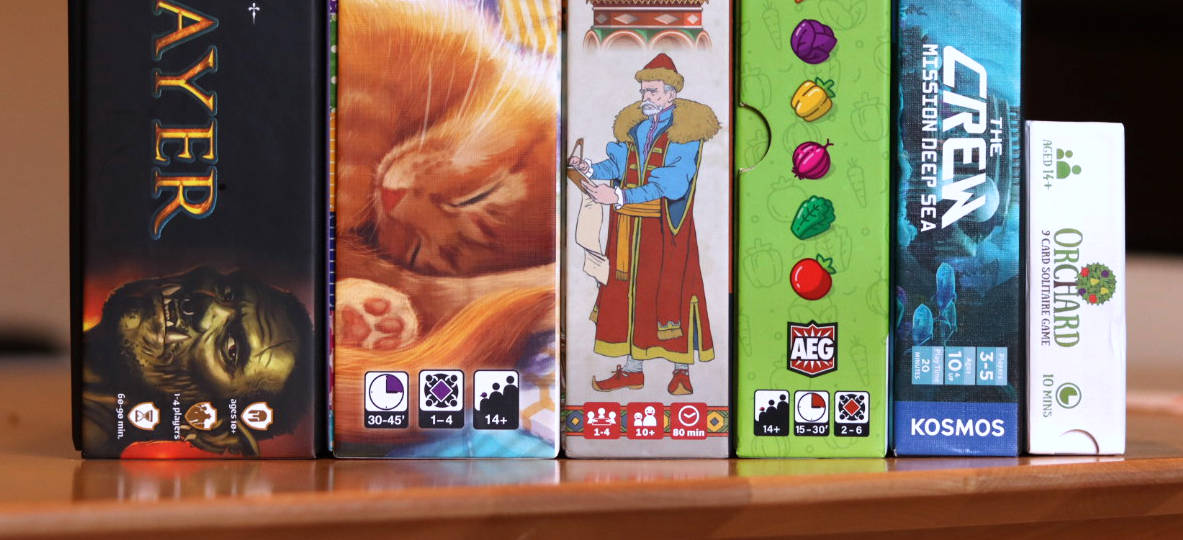

And still, if such a calculation feels like an impossible task given the interactive nature of the medium and the gulf of player ability, there’s already a major sector of the interactive field that has proven its feasibility and benefits: board games.

Weighing It Out

As a standard in tabletop gaming, game boxes have their estimated play times printed on them for easy reference. Why? When you’re planning a session with some friends, it’s helpful to be able to see at a glance how long a game session is likely to take, on average (as well as recommended player counts and age ranges). It would be detrimental to the hobby if this information wasn’t on hand. Additionally, sites like BoardGameGeek have established a community-aggregated Weight (or Complexity) rating on a scale from 1 to 5 that measures a myriad of factors that roughly translates to the level of preparation, investment, and skill required to play them. This extra metric is incredibly helpful when considering how alert and willing your game group is to engage with something that might bear a greater cognitive load. For example, a game like Point Salad (1.18) can be taught, set-up, played, and packed away in 30 minutes. On the heavier side, for The Gallerist (4.26), you’re likely spending 30 minutes watching a rules overview video before committing the next 2 to 3 hours playing it.

There’s a general correlation between board game complexity ratings and estimated play times, but there’s always exceptions to the rule. It also depends on the players at the table, their experience levels, and their penchant for certain types of games or mechanics.

What’s interesting to me here is that despite their differences, each weight category (lightweight, midweight, heavyweight) has their own place at the table that function as near-complements to each other more than as direct competition. People who love The Gallerist are likely to look for more heavy games for their collection. Those heavy games will compete in their own weight category. But those players will also be looking for lighter experiences to round out their play sessions: lightweight games to play ahead of or in between longer games, or midweight games that can offer similarly crunchy decision-making in a slightly smaller, speedier package. Typically, tabletop players know that each weight category serves a different purpose at the table and often fill their collections with a variety of them to best serve their players’s needs. With the ease of playing and discovering new games at every weight class, the availability of these metrics help both players and designers alike.

Yet with video games, it feels as if every game has been flattened down to compete on a level playing field based solely on genre and price. As examples, Chicory, Valheim, and Totally Accurate Battle Simulator cost the same amount but offer dizzyingly different gaming experiences. Minecraft Dungeons, Paper Mario: The Origami King, and Genshin Impact are all action role-playing games with incredibly varied game lengths. And all of these games are collected under the generic category of VIDEO GAME with no other helpful sign posts. If we could agree on formal genres to convey a game’s overall length like other media has done, perhaps it can help with discoverability, demand, and completion rates, much as it has done for board games.

Unlocking Potential

How exactly does improved discoverability factor in here? Imagine if, as a player, you know in advance how much free time you’ll have. What if you could quickly filter games that match that criteria? Adding a formal category for games that take, for example, 0-1 hours to beat, 1-4 hours, 4-8 hours, 8-20 hours, or 20 hours and up can easily resolve this. Even for match- or run-based games, such as most multiplayer or roguelike games, having a way to compare the average session length can help us fit them into our daily lives. And when we’re ready to move on to the next game, standout titles are less likely to get lost in the shuffle. Most store pages can already filter by price, rating, player counts, and genre, so why not length too?

Going one step further, if potential consumers can accept the idea of formal genres, wouldn’t it also stand to reason that it’d be easier to demand more games of a similar vein? It happened recently with the Battle Royale game. With the popularity of PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds, players learned a new term that defined a particular experience and set of mechanics. Armed with this knowledge, players were then able to create demand for more games of that exact type while developers sought to provide more of those experiences for consumers to fulfil their needs (what’s called “market pull”). The same can be said about Rob Daviau and the creation of the Legacy board game category, which continues to see a surge of innovation and creativity within that space. By having a consensus on formal genres for different lengths of play, the industry can hope for consumers who are better equipped to drive market pull for certain types of experiences while also proving the sales viability for hesitant developers.

So What’s Next?

At the end of the day, it just seems curious to me that we have yet to allow players to filter and search for narrative games by their length, let alone agree on formal genres for them. And yet we continue to define and identify new mechanics and genres whenever a pattern emerges. It’d be a simple thing to look to our literary siblings and adopt Quick games (0-1h), Short games (1-4h), Novella games (4-8h), Novel games (8-20h) and Epic or Saga games (20h+) into popular use. Or why limit ourselves to an imitation of another medium when we can choose our own paths, calling these formal genres Charms, Séances, or Spells for their immersive qualities? Or Beds, Gardens, Parks, and Forests for the spaces of play that developers cultivate for their players?

Regardless, for all the talk about how far the video game medium has come and the arc of its maturation, we are still struggling to equip our players with a better sense of how much time they’re likely to spend with a specific title. This isn’t about pinning times to an exact number nor is it about pushing the industry to make shorter games. Rather, it’s an opportunity to more fully consider our relationship with games, the responsibilities of the industry, and the scope of possible experiences they have yet to offer.

The novella fulfilled a need at a time when both writers and readers were seeking new experiences, ones more substantial than a short story and more digestible than a novel. So why can’t games have that too?

1. Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. "novella". Encyclopedia Britannica, 19 Apr. 2018, https://www.britannica.com/art/novella. Accessed 11 July 2022.↩

2. Good, Graham. “Notes on the Novella.” NOVEL: A Forum on Fiction, vol. 10, no. 3, 1977, pp. 197–211. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1345448. Accessed 11 Jul. 2022.↩