What's in a Mother?

- June 18 2022

- 9 min read

Eastward is a 2D action-adventure RPG that follows a father-daughter duo as they try to outrun an ever-encroaching threat while learning more about the world (and people) around them. The visuals are stunning, the music is stellar, and aside from some bloat, the game has some real stand-out moments. There’s extraordinary attention to detail when it comes to the character acting and staging, and the locations feel lived-in and inviting in a way that not a lot of post-apocalyptic settings do.

In Game Informer’s review, they write, “an excellent score provides an incredible backdrop to pixel-perfect art, creating a whimsical and enchanting atmosphere for this quirky RPG that openly pays homage to titles like Earthbound.” PC Gamer notes its inspirations, citing, “old RPGs and the likes of Earthbound, Zelda, and Studio Ghibli films.” Polygon’s review is titled, “Eastward is equal parts, Zelda, EarthBound, and itself.” Rock Paper Shotgun feels Eastward, “owes as much to the action of top-down Zelda games as it does to the role-playing intimacy of Earthbound.” Screenrant calls it, “a meticulously constructed puzzle-action RPG seemingly inspired most by the classic EarthBound/Mother series.” Hmm. Hold on a minute.

The Zelda inspiration is apparent in its combat and puzzle-dungeons. The Ghibli inspiration? Apart from a character that’s literally a Hayao Miyazaki stand-in, sure. I can see it. The visuals have nods towards Castle in the Sky, Howl’s Moving Castle, and Spirited Away. But the Mother series? As someone who finally played through all of Earthbound and Mother 3 in 2021, that comparison doesn't feel apt.

So what could these media outlets mean when they reference Earthbound? Are they simply using it as short-hand to describe a game that’s “quirky” or that has “offbeat humour”? Is it describing a game that has the potential to be a cult favourite? Or simply to say it’s an RPG that puts more focus on story and narrative than gameplay? Even if all of those points are true, all of these descriptors feel like they barely delve into what makes the Mother games really special. Henrique Lage says it best when he writes, “comparing a game to Earthbound has become the equivalent of comparing any game to Dark Souls (2009): almost a cliché, a sort of critical wildcard for not delving deeper, unfair to the works that find in that comparison the impossibility of being judged on their own terms.”

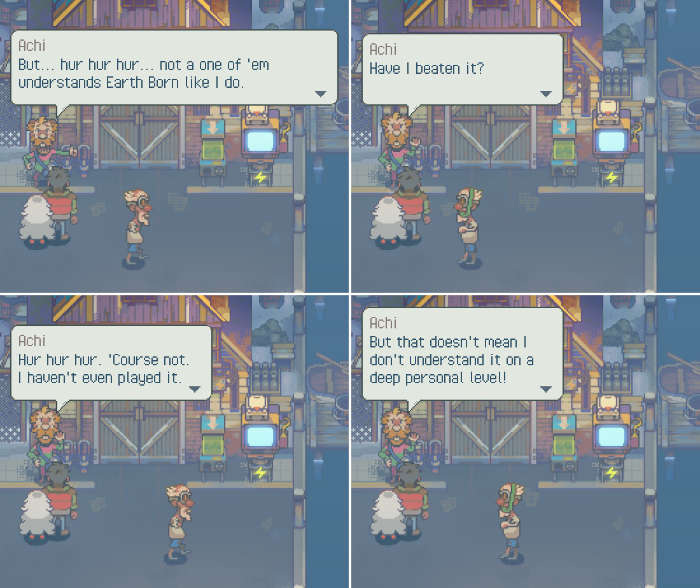

Eastward's "game-within-a-game" Earth Born, both in how it alludes to its own influences and how it comments on our relationship with these games, is one of my favourite parts.

Let’s delve deeper, then. I want to understand what makes the Mother games Motherlike because not doing so feels like a disservice to the games themselves. It’s a worthwhile exercise, as players, to better reflect on our own experiences. I hope that by understanding these core features we can better map their influence on other games, and to find new titles in its lineage that do more than simply pay homage. Granted, game genres already tend to be “weirdly unhelpful, mechanical, and self-referential,” as Kate Gray explains, such as the ever-growing and contentious Roguelike tag, but there’s still value to potential players to find titles that fall roughly under the same categorical umbrella. And in this post, I hope to avoid specific game mechanics or systems and to focus more on the overall structure or feeling that the Mother games communicate.

So, what exactly makes the Mother games Mother-like?

Playfulness and Self-awareness

“Mother was a videogame,” writes Tim Rogers in his review. “Mother 2 lets you know that it knows you're playing it as a videogame.” The self-awareness in the Mother series is playful in ways that draw attention to itself as an interactive medium and to our relationship to it. Shigesato Itoi, being no stranger to postmodernism and the video game conventions of his time, is aware of how every design decision affects and is affected by his audience.

These games use established genre conventions (in this case, the one popularized by the likes of Dragon Quest) as a framework to push back against our assumptions, such as quest or narrative structures or the contents of treasure chests. And more than just commenting on them, they also set out to improve the core experiences of the games they’re riffing on, such as the ability to see enemies in the overworld and the rolling HP meter in Earthbound, or the bonus rhythm minigame in Mother 3’s battles.

Most importantly, the game wields its self-awareness in an attempt to deepen our connection with its characters throughout the game’s events and to share in the joy and thrills of what videogames can offer, as opposed to other modern self-aware games that may use that same awareness to simply seem clever or mock its own medium.

Stylized, Iconic Visuals

Despite more contemporary titles, such as Final Fantasy VI, demonstrating the gradual mastery of console pixel art, the Earthbound development team intentionally decided on cartoonier and simpler visuals. When development for Mother 3 switched from the SNES to the N64 (and then later to the 64DD add-on), they tried to push the graphics further to take advantage of the new hardware, making the game more technically complex… before scrapping it all and going back to its cartoony roots. They even released it on a handheld system that was nearing the end of its life-span (there’s a full interview here between Shigesato Itoi, Shigeru Miyamoto, and Satoru Iwata about Mother 3’s development that’s incredibly frank. It’s a great read).

They had a good reason for this decision, too: developers had experience getting the most out of the GBA hardware at this point, its portability was a great way to draw in new potential players (and non-gamers), and reverting back to Earthbound’s visual style helped fans link it back to their memories of the series. On top of that, games with stylized visuals have their own kind of lasting power far greater than anything that strives for realism, and they work well as a juxtaposition against the Mother games' more serious or shocking moments. And as any animation fan can tell you, works that are made to look more “cartoony” can still deliver incredibly impactful scenes and emotional gut-punches.

Pointed Commentary

A lot of Earthbound players will fondly remember using the Pencil Eraser, searching for sesame seeds in a desert, or fighting enemies like Abstract Art. But what about the moment when Onett’s police take a child into the back of the precinct and assault him, one by one? Or Ness’s gradual loss of innocence as he ventures further out from home? Or the feeling of absolute despair during the game’s final battle? What about Tazmily in Mother 3 and the changes it undergoes throughout the game?

Earthbound says, "ACAB"

More than just a power fantasy or a meaningless romp, these games have something to say about larger, external forces in our world: capitalism, imperialism, fascism, and the role of police were prime targets for these games. Compared to some AAA studios that claim that their military shooter games are somehow free from any political statement, it’s refreshing to see a game have an actual voice (despite its treatment of queer and trans characters in Mother 3). It’s probably also one of the reasons why Nintendo will likely never release Mother 3 outside of Japan.

Balance of Humour and Pathos

Mother 3 deals with grief, pain, and anger. It shows us a world at peace and the way that it can slowly corrupt, hollowing itself from the inside out. The game also goes on to expose the lies that this little world was initially built on, and the lessons that its people sought to forget. It also has an enemy called a Horsantula and treasure chests that fart when you open them. They may seem at odds with each other, but the balance of humour and pathos in the Mother games is essential to the experience.

Balancing the lighter and darker moments of the story allows each part on its own to have more impact, similar to the way that elements of comedy and horror play well against each other in film. As tension builds, comedy can help relieve the audience’s pressure before building it back up again. Or it can play with our expectations in inventive ways. There’s also a particular thrill that comes from never quite knowing what’s around the next corner, such as a Chimera or a comically large toilet. And by framing the events and settings of its games through the eyes of children, the Mother games are able to broach difficult topics in accessible ways while also adding genuine warmth and whimsy.

Writerly

A lot of essays about Earthbound and Mother 3 I’ve come across compare them to literature or discuss its literary qualities. The comparison isn’t surprising given the care that’s gone into the dialogue and flavour text and their overall story structures: Earthbound is one part road movie, one part coming-of-age story, with a surreal touch; Mother 3 is the saga of a single family overcoming grief that often feels more like an intimate stage-play than a novel. In this way, one defining feature of the Mother games is what I can only describe as being “writerly,” that is, being consciously literary in its execution or ambition.

Okay, that sounds a little pretentious, but please bear with me. For video game developers, they often look to other video games for inspiration, creating an insular media ecosystem. In the same way that story genres can use tropes to convey meaning to its audience more efficiently, so too do games rely on players bringing with them pre-existing knowledge on how to play. There’s a literacy that a lot of games depend on. Developers can’t help but pull from other examples in the medium because it takes the responsibility away from them to explain everything all over again (such as “move to the left,” or “treasure chests can be opened”). So when someone comes along from outside the medium, especially with a literary background and a modern eye, they may be better equipped to question a lot of the baseline design assumptions we creators take for granted. In Tim Rogers’ review of Mother 3, he writes,

“Usually, [programmers are] thinking of the game design and the story simultaneously. They're thinking of reasons to get the characters into a spaceship so there can be an action scene on a spaceship, because they've already got a spaceship environment half coded, et cetera. When you get a writer who comes from outside the game field, they might end up constructing a story that will present design challenges. [Kaori] Kurosaki, in her Wild Arms V scenario, for example, makes it the goal of the first "dungeon" to escort your female childhood friend to the place where you first met (sort of) so you can tell her that you're planning on leaving the village. In other words, it uses characters' emotions as a goal for an in-game task. It's subtle, though hardly invisible: the story and the game design are rubbing against one another, and creating emotive friction. It's nice.”

That writerly mindset is exactly what informs the countless little decisions that help make the Mother games stand out. What’s more, it creates an interesting little paradox (as pointed out by my friend Meghan): games that pull heavily from the Mother series can’t be Motherlikes, no matter how close they try to recreate them, because they lock themselves back into that insular media ecosystem. Mother games, by their nature, are outsider perspectives.

★

So with all that said and done, how do these criteria stack up against Eastward? Overall, it feels to me that Mother’s influence isn’t as strong here. The visuals are its most defining feature. The self-awareness shines through with the moments around Earthborn, the game-within-the-game that all of its citizens know and play, but not as much during the main game. The darker subject matter in the story ebbs and flows to make way for some really tender and silly moments. But Eastward neither strives to be writerly nor to make any consistent, pointed commentary about larger social or political forces. It’s its own thing, for sure, but Eastward is still an amalgamation of a lot of other games the developers love, and they’re not shy about bringing those influences to the forefront (for better or worse) instead of blurring the seams.

One of Eastward's many "blink-and-you-miss-it" NPC interactions. This character seems to ring a bell...

Surprisingly, after writing this post, one game came to mind as an excellent example of a modern Motherlike: Kentucky Route Zero. It fits all of the above criteria, as well as other minor points like having a rotating cast of main characters, a modern setting, and an episodic format. It’s surreal, it has a lot to say about debt and labour, it draws from the art exhibition world and interactive art history, and there’s genuine humour and heart at its core. KRZ might be the closest thing to a Motherlike we’ve had for a while (even more than Undertale), and if you haven’t played it yet, consider this the strongest recommendation I can give. KRZ is really good.

What other games do you consider to be Motherlike? Focusing on its voice rather than specific mechanics, are there any other qualities Motherlikes share? Let me know below!

★

Special thanks to Meghan Lands for the feedback, and Charlie Bryant for being my Mother buddy during the past couple of years